A research team from the University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography has completed the first high-resolution, bathymetric (bottom-depth) survey of Wassaw Sound in Chatham County.

Led by Skidaway Institute scientist Clark Alexander, the team produced a detailed picture of the bottom of Wassaw Sound, the Wilmington River and other connected waterways. The yearlong project was developed in conjunction with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

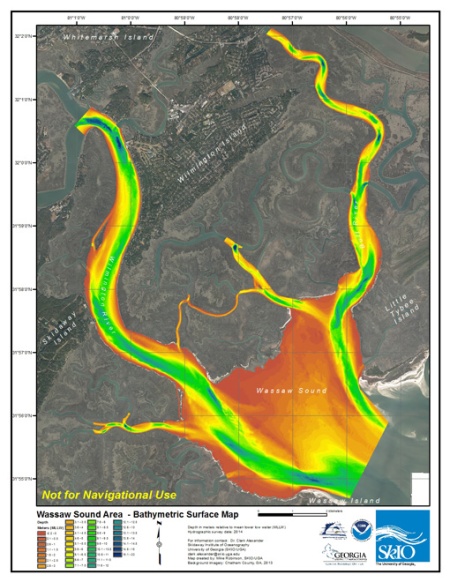

This shows a wide view of the Wassaw Sound survey map. Shallow areas are shown in orange and yellow, deeper areas in green and blue.

The survey provides detailed information about the depth and character of the sound’s bottom. This information will be useful to boaters, but boating safety was not the primary aim of the project. The primary objective was to map bottom habitats for fisheries managers. DNR conducts fish surveys in Georgia sounds, but, according to Alexander, they have limited knowledge of what the bottom is like. “One of the products we developed is an extrapolated bottom character map,” Alexander said. “This describes what the bottom grain size is like throughout the sound. Is it coarse, or shelly or muddy? This is very important in terms of what kind of habitat there is for marine life.”

A second goal was to provide detailed bathymetric data to incorporate into computer models that predict storm surge flooding caused by hurricanes and other major storms. Agencies like the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration use mathematical models to predict anticipated storm inundation and flooding for specific coastal areas. A key factor in an accurate modeling exercise is the bathymetry of the coastal waters.

“You need to know how the water will pile up, how it will be diverted and how it will be affected by the bottom morphology,” Alexander said. “Since we have a gently dipping coastal plain, storm inundation can reach far inland. It is important to get it as right as we can so the models will provide us with a better estimate of where storm inundation and flooding will occur.”

Funded by an $80,000 Coastal Incentive Grant from DNR, Alexander and his research team, consisting of Mike Robinson and Claudia Venherm, used a cutting-edge interferometric side-scan sonar system to collect bathymetry data. The sonar transmitter/receiver was attached to a pole and lowered into the water from Skidaway Institute’s 28-foot Research Vessel Jack Blanton. Unlike a conventional fishfinder, which uses a single pinger to measure depth under a boat, the Edgetech 4600 sonar array uses fan-shaped sonar beams to both determine water depth and bottom reflectivity, which identifies sediment type, rocky outcroppings and bedforms, in a swath across the boat’s direction of travel.

Skidaway Institute of Oceanography research coordinator Claudia Venherm logs survey activity on board the R/V Jack Blanton

The actual process of surveying the sound involved long hours of slowly driving the boat back and forth on long parallel tracks. On each leg, the sonar produced a long, narrow strip indicating the depth and character of the sound bottom. Using high-resolution Global Positioning System data that pinpointed the boat’s exact location, the system assembled the digital strips of data into a complete picture of the survey area.

All the other sounds on the Georgia coast were mapped in 1933, but for some reason data from that time period for Wassaw Sound was unavailable. When the team began this project, they believed they were conducting the first survey of the sound. However, just as the researchers were finishing the project, NOAA released data from a 1994 single-beam survey that had been conducted in advance of the 1996 Olympic yachting races that were held in and near Wassaw Sound.

“This worked out very well for our project, because we are able to compare the differences between the two surveys conducted 20 years apart,” Alexander said. “We see areas that have accumulated sediment by more than 2 meters, and we also see areas that have eroded more than 2 meters since 1994. Channels have shifted and bars have grown or been destroyed.”

Because of advances in technology, the current survey is significantly richer in detail than the one conducted in 1994. “We can zoom down to a square 25 centimeters (less than a foot) on a side and know the bottom depth,” Alexander said.

The survey produced a number of findings that were surprising. The intersection of Turner Creek and the Wilmington River is a deep, busy waterway. Although most of the area is deep, the survey revealed several pinnacles sticking up 20 feet off the bottom. “They are round and somewhat flat, almost like underwater mesas,” Alexander said.

The researchers determined that the deepest place mapped in the study area was a very steep-sided hole, 23 meters deep, in the Half Moon River where it is joined by a smaller tidal creek. They also found several sunken barges and other vessels.

The survey data set is available to the public on the Georgia Coastal Hazards Portal at http://gchp.skio.usg.edu/. Alexander warns that while boaters should find the survey interesting, the information is intended for habitat research and storm surge modeling, not for navigation. “Because the bottom of Wassaw Sound is always shifting and changing, as our survey showed, don’t rely on the data for safe navigation,” he cautioned.

Alexander has already received a grant for an additional survey, this time of Ossabaw Sound, the next sound south of Wassaw Sound. He expects work to begin on that survey in early 2015.

The Skidaway Institute of Oceanography is a research unit of the University of Georgia located on Skidaway Island near Savannah. The mission of the institute is to provide the state of Georgia with a nationally and internationally recognized center of excellence in marine science through research and education.