In the battlefield of the microbial ocean, scientists have known for some time that certain bacteria can exude chemicals that kill single-cell marine plants, known as phytoplankton. However, the identification of these chemical compounds and the reason why bacteria are producing these lethal compounds has been challenging.

Now, University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography scientist Elizabeth Harvey is leading a team of researchers that has received a $904,200 grant from the National Science Foundation to fund a three-year study into the mechanisms that drive bacteria-phytoplankton dynamics.

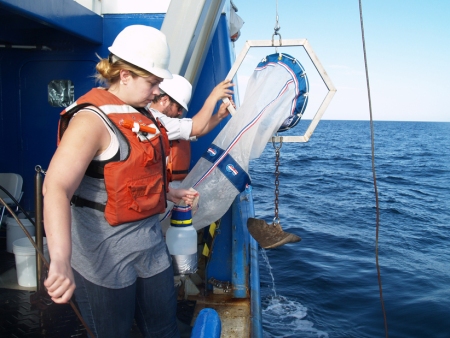

Researcher Elizabeth Harvey examines a part of her phytoplankton collection.

Understanding these dynamics is important, as phytoplankton are essential contributors to all marine life. Phytoplankton form the base of the marine food chain, and, as plants, produce approximately half of the world’s oxygen.

“Bacteria that interact with phytoplankton and cause their mortality could potentially play a large role in influencing the abundance and distribution of phytoplankton in the world ocean,” Harvey said. “We are interested in understanding this process so we can better predict fisheries health and the general health of the ocean.”

This project is a continuation of research conducted by Harvey and co-team leader Kristen Whalen of Haverford College when they were post-doctoral fellows at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. They wanted to understand how one particular bacteria species impacted phytoplankton.

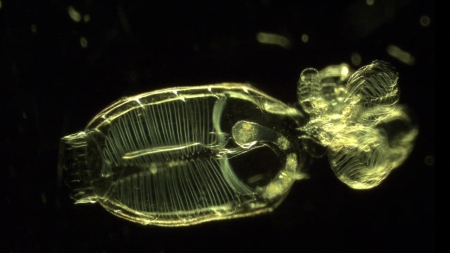

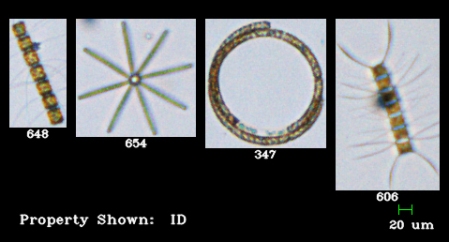

A microscopic view of a population of phytoplankton

“We added the bacteria to the phytoplankton and the phytoplankton died,” Harvey said. “So we became very interested in finding the mechanism that caused that mortality.”

They identified a particular compound, 2-heptyl-4-quinlone or HHQ, that was killing the phytoplankton. HHQ is well known in the medical field where it is associated with a bacterium that can cause lung infections, but it had not been seen before in the ocean. The team will conduct laboratory experiments to determine the environmental factors driving HHQ production in marine bacteria; establish a mechanism of how the chemical kills phytoplankton; and use field-based experiments to understand how HHQ influences the population dynamics of bacteria and phytoplankton.

“This project has the potential to significantly change our understanding of how bacteria and phytoplankton chemically communicate in the ocean.” Harvey said.

The project will also include a strong education component. The researchers will recruit undergraduate students, with an effort to target recruitment of traditionally under-represented groups, to participate in an intense summer learning experience with research, field-based exercises and some classroom work.

“The idea is for the students to return to their home institutions at the end of the summer, but to continue to work with us on this project,” Harvey said. “This will be a unique opportunity to offer students cross disciplinary training in ecology, chemistry, microbiology, physiology and oceanography.”

In addition to Harvey and Whalen, the research team includes David Rowley of the University of Rhode Island.

NOTE: A complementary video with an interview with Dr. Harvey is available at http://www.skio.uga.edu/news/videos/

“You may have learned in school that photosynthesis is how plants use sunlight to turn water into hydrogen and carbon dioxide, its food, and oxygen, which it releases into the air for all of us to breathe. But photosynthesis doesn’t just happen on land – it happens in the ocean.

“You may have learned in school that photosynthesis is how plants use sunlight to turn water into hydrogen and carbon dioxide, its food, and oxygen, which it releases into the air for all of us to breathe. But photosynthesis doesn’t just happen on land – it happens in the ocean.