Posts Tagged ‘zooplankton’

Tiny but voracious marine organism studied — video

February 8, 2017Tiny but all-consuming marine organism focus of UGA Skidaway Institute study

February 8, 2017

Marc Frischer

Doliolids are tiny marine animals rarely seen by humans outside a research setting, yet they are key players in the marine ecosystem, particularly in the ocean’s highly productive tropical and subtropical continental margins, such as Georgia’s continental shelf. University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography scientist Marc Frischer is leading a team of researchers investigating doliolids’ role as a predator in the marine food web.

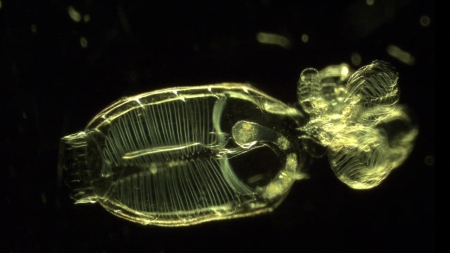

Doliolids are small, barrel-shaped gelatinous organisms that can grow as large as ten millimeters, or about four tenths of an inch. They are not always present in large numbers, but when they bloom they can restructure the marine food web, consuming virtually all the algae and much of the smaller zooplankton.

A doliolid with a cluster of juvenile doliolids on its tail. Actual size is approximately three millimeters, or one eighth inch.

“The goal of this particular study is to find out what the doliolids are eating quantitatively,” Frischer said. “This is so we can understand where they fit in the food web.”

Scientists know from laboratory experiments what doliolids are capable of eating, but they don’t know what they actually do eat in the wild. They are capable of eating organisms as small as bacteria all the way up to much larger organisms.

“What they are eating and how much are they eating from the smorgasbord that is available to them, that is the question,” Frischer said. “We are investigating how much of those different prey types they are really eating out there across the seasons.”

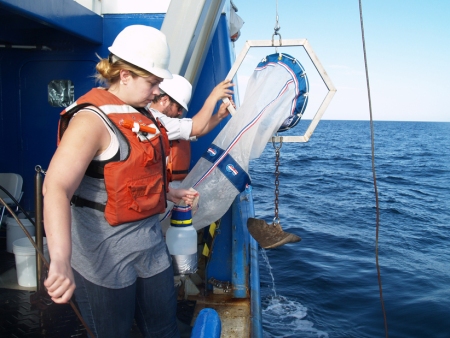

The project involves intensive field work, including 54 days of ship time on board UGA Skidaway Institute’s Research Vessel Savannah. During the cruises they conduct trawls using special plankton nets to collect the doliolids. They also collect water samples to understand the conditions where the doliolids thrive.

Graduate students Lauren Lamboley and Nick Castellane deploy a plankton net from the Research Vessel Savannah.

“We take the doliolids and the water samples back to the laboratory, and that is where the magic begins,” Tina Walters, Frischer’s laboratory manager said.

Because the animals are gelatinous and very delicate, the researchers cannot use classical microscopic techniques to dissect the animals and analyze their gut content. Instead they extract DNA from the animals’ gut and use sequence-based information to determine what the doliolid ate.

“We go through a process called quantitative PCR,” Walters said. “So even though we can’t see the prey in a doliolid’s gut, because the prey have unique DNA sequences, we can identify and quantify them using a molecular approach.”

The three-year project is funded by a $725,000 grant from the National Science Foundation and will run until February 2018. Frischer’s collaborator on the project is Deidre Gibson from Hampton University. Gibson received her Ph.D. from the University of Georgia in 2000, and did much of her graduate research at Skidaway Institute with Professor Gustav Paffenhöfer. In addition to Walters, Savannah State University graduate student Lauren Lamboley is part of the team, along with a number of students at Hampton University. Several undergraduate research interns have also participated in the project, gaining hands-on research experience. Frischer is also working with the Institute for Interdisciplinary STEM Education at Georgia Southern University to engage K-12 teachers by inviting them to participate in the research cruises.

Congratulations…

March 28, 2013… to Skidaway Institute tech Tina Waters! She won a student poster award at the ASLO meeting held in New Orleans last month. The title of her winning poster is:

MOLECULAR PROFILING OF ZOOPLANKTON GUT CONTENT USING PNA-PCR AND DENATURING HIGH PERFORMANCE LIQUID CHROMATOGRAPHY (PNA-PCR-DHPLC)

LaGina M. Frazier, Gustav-A. Paffenhöfer, and Marc E. Frischer all collaborated with Tina and were cited on the poster. In addition to being a valued member of the Skidaway Institute science team, Tina is a grad student at Savannah State.